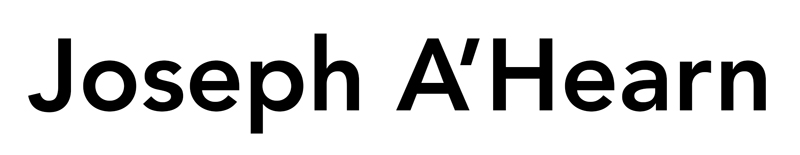

Because circumpolar constellations by definition never go below the horizon, classifying constellations as circumpolar is subject to one’s latitude. From the Equator no constellations are circumpolar, whereas from the North Pole all constellations above the horizon are also circumpolar.

The constellations I’ve selected for this list are the closest ones to the North Celestial Pole, which I’ve become quite familiar with by living most of my life above the 40th parallel north. Although the full list strictly applies to only roughly 13% of the world’s population, it will still loosely apply also to the half of the world’s population that lives between the 20th and 40th parallels north (see Kummu and Varis 2011 for a global analysis of human population by latitudes). The bottom line is that most people can see these constellations for much of the year. This list is also based on my observational experience rather than on the strict calculation of 90 degrees minus their southernmost declination.

Note: This and all the images below are screenshots I took from the free Stellarium software. I have been using it for years and encourage you to use it too.

1. Ursa Major

Ursa Major is Latin for the Greater Bear. Imagining this constellation as a bear even goes back further, at least to Homer, who called it Arktos, which is Greek for bear. Ursa Major is technically more southern than the rest of the constellations I’m classifying as circumpolar, being circumpolar only at and above 62 degrees north. Nevertheless, it would not make sense to leave it off this list because the part of it called the Big Dipper is the most recognizable asterism (pattern of stars) in the celestial sphere, and the Big Dipper becomes circumpolar at and above 41 degrees north.

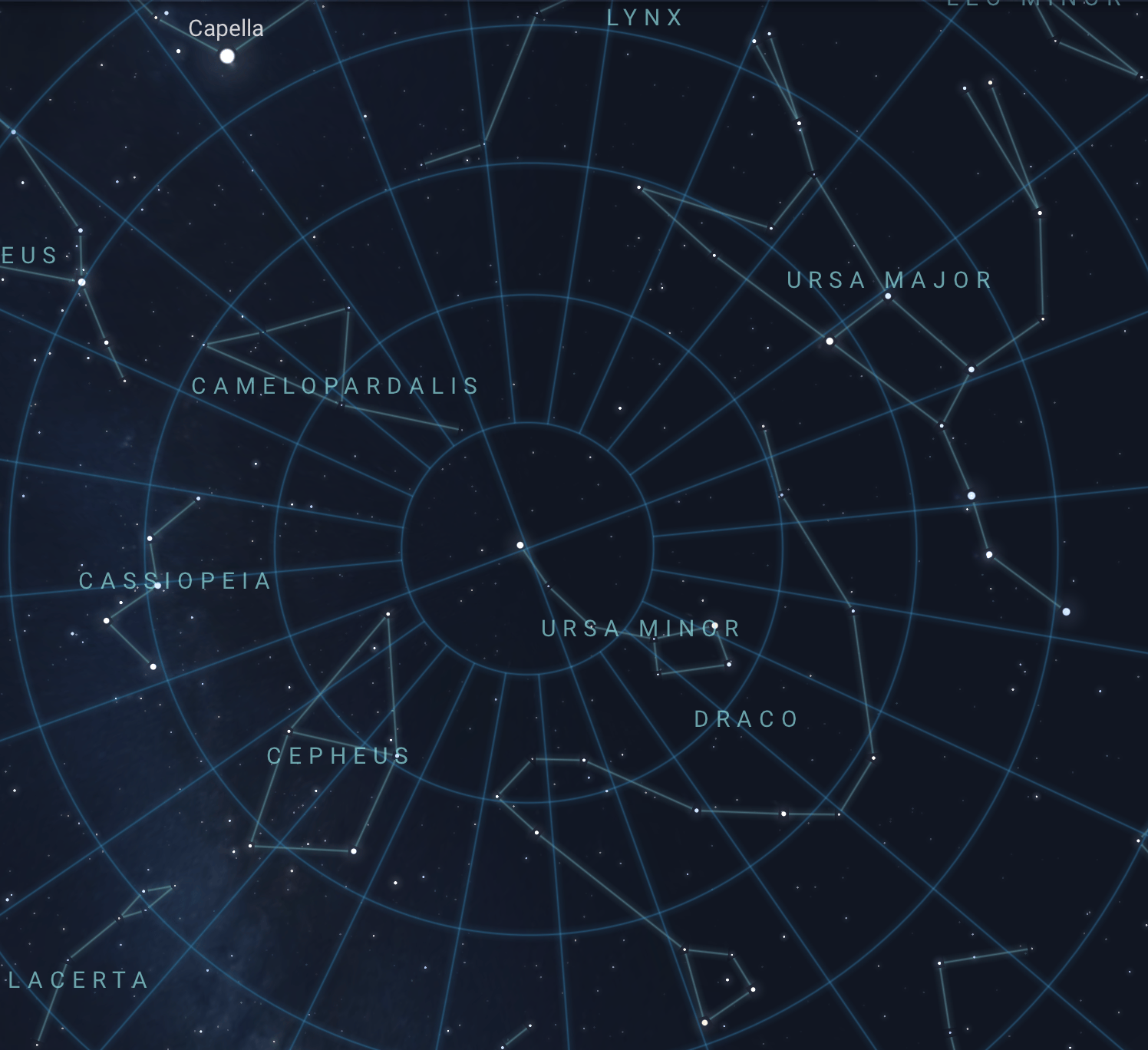

The Big Dipper is the tail and back part of the torso of the Ursa Major. The two stars that make up the tip of the Big Dipper point to Polaris, so they are also known as the Pointers. Less known but also useful is that the handle of the Big Dipper can also be extended in a curvilinear fashion to arrive at the bright star Arcturus in Boötes (most easily seen in the Spring). In this way the Big Dipper is associated with the two mnemonic phrases “Point to Polaris” and “Arc to Arcturus”.

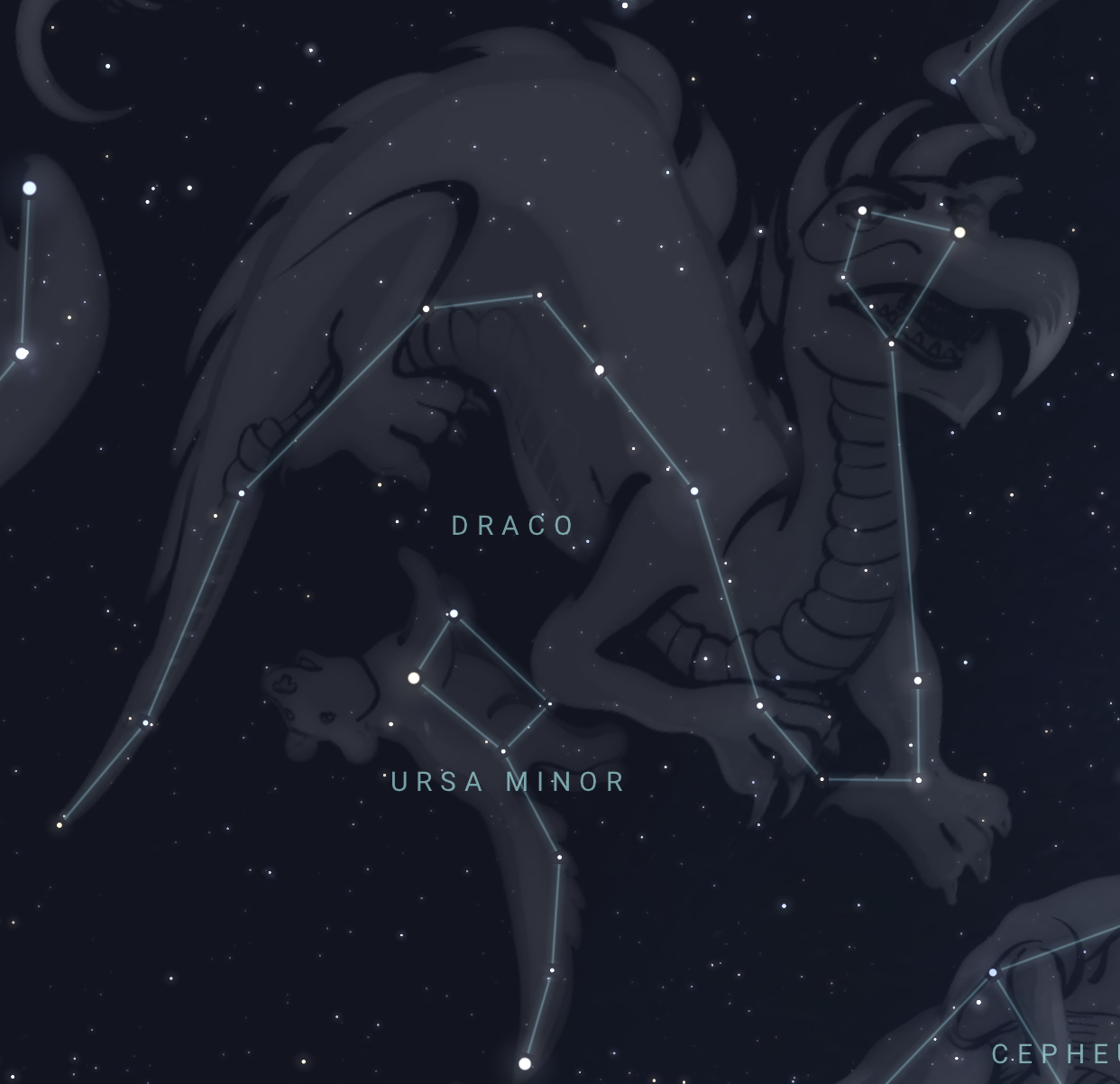

2. Ursa Minor

Ursa Minor, Latin for the Lesser Bear, is especially significant because Polaris is currently the North Star and will continue to be the closest bright star to the North Celestial Pole until around AD 3200 (look up the Precession of the Equinoxes to dive into this motion that takes around 26,000 years to complete a cycle). Ursa Minor becomes circumpolar at and above 25 degrees north, and is thus the farthest north of all constellations. Ursa Minor is also known as the Little Dipper, and, in this case, there is no difference in what stars are included by referring to it as the Little Dipper.

3. Cassiopeia

It’s easy to find “the W” in the North. That would be Cassiopeia, named after the vain mythological Queen of Ethiopia, wife of Cepheus, and mother of Andromeda. Cassiopeia becomes circumpolar at and above 43 degrees north. Because Cassiopeia is on the opposite side of Polaris as the Big Dipper, it helps me figure out which way is north whenever I spot Cassiopeia first.

4. Cepheus

Cepheus is fainter than Cassiopeia but further north. I recognize Cepheus by associating its shape with that of a house. In mythology, however, Cepheus was the King of Ethiopia, husband of Cassopeia, and father of Andromeda. Cepheus becomes circumpolar at and above 32 degrees north.

The next three North Stars after Polaris will be stars of Cepheus: Errai (Gamma Cephei) for AD 3200-5200, Iota Cephei (dim enough that it doesn’t have a proper name) for AD 5200-7500, and Alderamin (Alpha Cephei) for AD 7500-8700.

5. Draco

Draco, circumpolar at and above 40 degrees north, surrounds half of Ursa Minor. Although Draco is Latin for dragon, Draco is identified with several different dragons in mythology. I usually find Draco by recognizing the group of four stars that make up the Head of Draco. Some observers also call this the Lozenge, while others say that the Lozenge is made up of three of these stars and one of the stars in Hercules, Iota Herculis (see Hercules in my blog post Learn the Northern Summer Constellations).

Minor Constellations

6. Lacerta

Lacerta, Latin for lizard, is circumpolar at and above 55 degrees north. Because it has no significantly bright stars, it is somewhat difficult to see. It might be easier to locate it by looking for the space between Cepheus and Pegasus or between Cygnus and Andromeda (see Cygnus in my blog post Learn the Northern Summer Constellations; Pegasus and Andromeda will be included in a future blog post Learn the Northern Fall Constellations)

7. Lynx

Lynx is aptly named because you need lynx-like eyes to spot it. It becomes circumpolar at and above 57 degrees north. It can be found by looking for the space between Ursa Major and Gemini and between Leo and Auriga.

8. Camelopardalis

Camelopardalis, Latin for giraffe, is one of the most difficult constellations to see. It is circumpolar at and above 37 degrees north. It can be found by looking for the space between Cassiopeia and Ursa Major, between Ursa Minor and Persus, and between Cepheus and Auriga.

To complement this list of the northern circumpolar constellations, I have lists of the constellations to learn in each season. See my post here on the northern Summer constellations. Others are still to come.